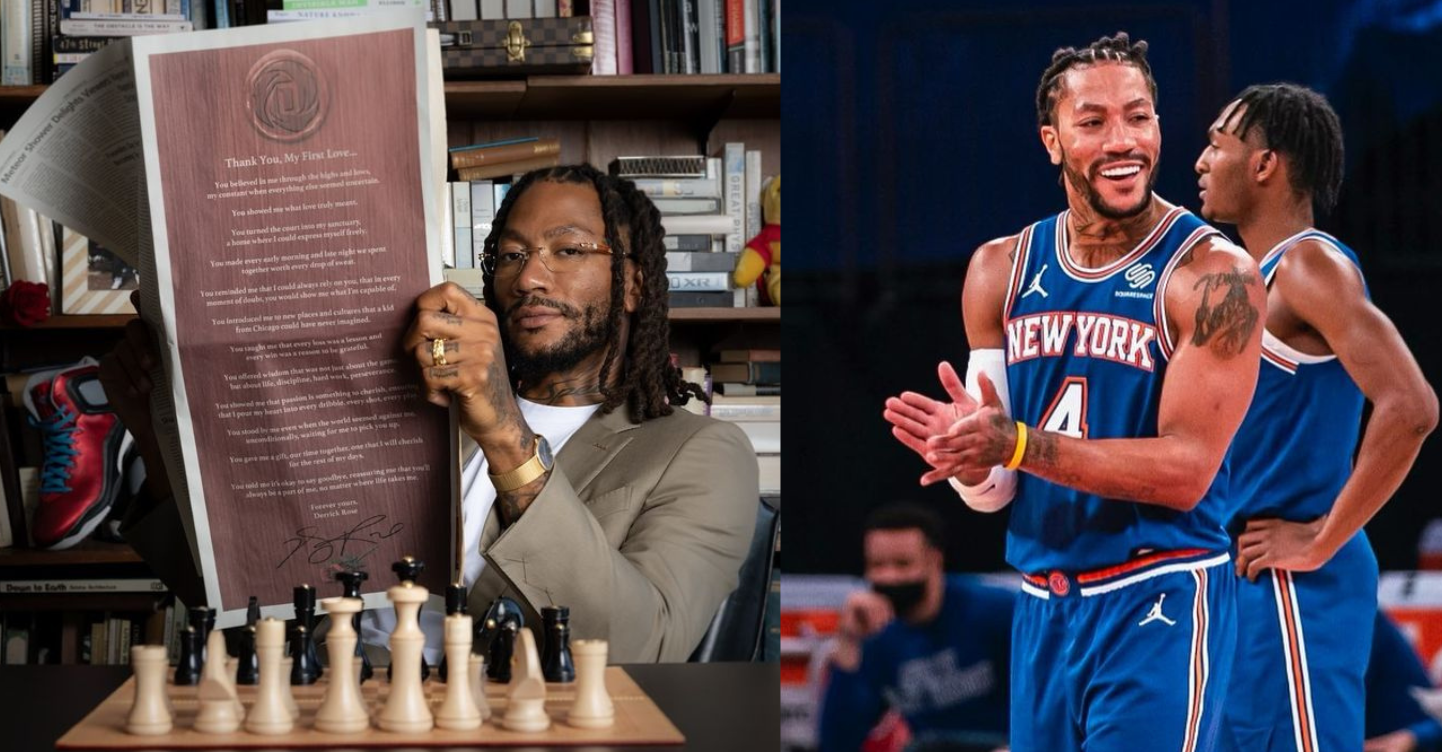

Derrick Rose Announces Retirement From NBA: “It’s okay to say goodbye”

Food Voyages: Six journeys in search of a single bite.

I used to take pride in eating the hottest chiles I could. I went up the ranks of the Scoville scale, dosing myself with Thai bird chiles, Scotch bonnets, habaneros, Trinidad Moruga scorpions and bhut jolokias, also known as ghost peppers, whose intensity is so great, the Indian military has reportedly used them to develop a kind of tear-gas grenade.

This is how most Americans view chiles. In the wildly popular YouTube series “Hot Ones,” celebrities attempt to eat soul-shatteringly spicy chicken wings.

Over time, I came to see the error of chile-eating as competitive sport. A chile is an ingredient, not just a vehicle of sensation (and suffering).

I began to wonder if I knew chiles at all.

So I flew to Peru to find out.

I wanted to taste a descendant of those ancient peppers, Peru’s native ají amarillo.

If I was going to truly understand chiles, this one — grown in the same region for ages, possessed of equal parts fire and flavor — might hold the key.

Here, twice a year, pale starlike flowers open, from which the chiles emerge.

Once harvested, some are trucked to market, while others end up at factories that turn them into a vital element in Peruvian cooking: salsa de ají amarillo. I visited one small factory to watch the process.

Workers in protective gear carry the chiles from one room to the next.

Now it was time to learn how this distillation of ají amarillo manifested in local dishes.

I started my quest at Isolina, a restaurant in the bohemian barrio Barranco that serves classics of criollo (creole) cuisine, drawing from Peru’s multiple traditions: Indigenous, colonial Spanish and African, passed down by enslaved people during the Spanish conquest.

The chile turned up in almost every dish, bringing a sly kick to stir-fried tenderloin and potatoes engulfed in two cheese sauces; a faint sweetness to counter the salty funk of sharp cheese in ají de gallina; a warm purr in a spill of leche de tigre over little fried silver fish; and a sunny leavening to tiers of mashed potatoes.

I could see why a colleague of mine, the journalist Nicholas Gill, had told me: “Ají amarillo is such a friendly chile. It uplifts everything.”

I wanted to find out how the chile gives character to another dish: tiradito, a cousin to ceviche, in which raw fish is cut long, into whisper-thin ribbons, like sashimi, and dressed in leche de tigre, a sauce golden with ají amarillo.

In the narrow kitchen of Rocio & Papacho, a makeshift restaurant on the pier, I watched the chef, Rocio Cuba, prepare the dish.

The tiradito was garlicky and punchy, the sultry halo of ají amarillo heightened by a brilliant sting of lime.

I felt as if this might be the closest I’d yet come to really tasting ají amarillo, its frank optimism, its essence as a fruit. But I needed more.

I headed to La Picantería, a rustic lunch-only spot in Surquillo that specializes in seafood and local dishes.

We started off with Pisco Sours, of course, in honor of the South American brandy.

We chose a hefty corvina, which appeared at our table with head, fins and tail intact but its middle transformed into jaladito, in which the fish is cut slightly thicker, cured with salt and then doused in leche de tigre, a pool of gold, with arcs of ají amarillo scattered on top.

Here the chile was even more vivid, like sun touching down at the bottom of the sea.

I couldn’t leave Lima without stopping by Maido, one of the most acclaimed restaurants in the world.

Chef Mitsuharu Tsumura made a tiradito with a trout from the fresh highland waters of the Andes.

This is it, I thought, this is ají amarillo.

But when I went back to the kitchen to thank Tsumura, he said I had to try one more dish to complete my quest, a humble soup, sudado, named after the process of “sweating” — that is, steaming — fish in hot broth.

We waited a moment for it to cool. Then I tasted a spoonful: all these little treasures gathered from across Peru, these gifts of land and sea, gilded by an ancient, essential and at the same time totally ordinary, everyday chile. This was the warmth of connectedness, of things falling into place.

“Hot Ones” videos from First We Feast.

Ligaya Mishan is a columnist for the magazine and a writer at large for T Magazine whose articles often use food as a lens for understanding culture. Luisa Dörr is a Brazilian photographer based in Bahia.

Publisher: Source link

Latest Posts

-

31 July 2025

-

26 July 2025

-

14 July 2025

-

01 July 2025

-

07 August 2025

-

29 July 2025

-

20 February 2025

-

04 February 2025

Newsletter

Sign up for free and be the first to get notified about new posts.

Get The Best Blog Stories into Your icountox!

Sign up for free and be the first to get notified about new posts.