10 Spots That Serve Delicious Ice Cream With Unique Flavors and Twists

Nostalgic for a time before ubiquitous connectivity, a writer ditched his phone and relied instead on serendipity — and maps made by people he met along the way.

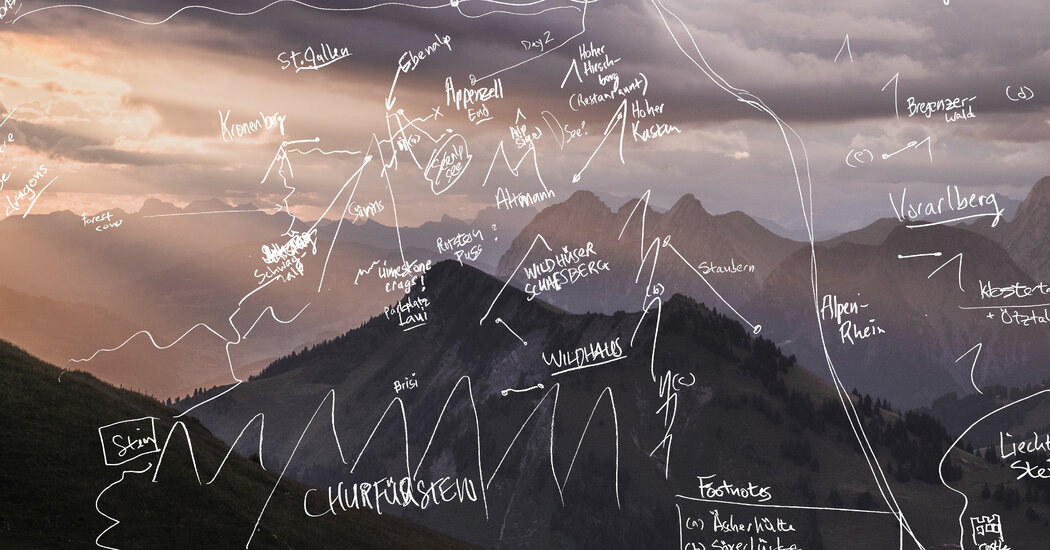

Photographs and Text by Ben Buckland

I hadn’t expected snow. But now it was blowing sideways, and the wind was strong enough that it was hard to stand. Clouds swirled around me. Visibility at a minimum. I was OK but felt close to the edge — closer than I’d expected on a summer day.

But this was also the day that Chris, an American sitting in a mountain hut, drew me the last sketch I would need, leading me all the way to Lake Constance and the Rhine. So perhaps the most difficult day was also the day I knew for sure that I would make it — that I’d find my way across Switzerland with nothing but the hand-drawn maps of strangers.

Last summer, frustrated with the predictability of recent travel experiences, I set out to walk across Switzerland without a phone or a preplanned route. I allotted 12 days, beginning on the shores of Lake Geneva, in the west, and heading in the general direction of Lake Constance, in the northeast — a distance, as the crow flies, of about 150 miles.

Nostalgic for the time before ubiquitous connectivity, when we relied on paper maps and conversations with strangers, I came up with a novel way to organize my trip: Each day, I planned to ask locals I met to sketch hand-drawn maps for me, which I would then follow as best I could.

I wanted to know if it was possible to walk across a country like this. I wanted to know what it would teach me about how technology and convenience have changed the way we travel. I wanted to be lost, and to find my way through the artwork of strangers.

Day 1 5 miles, from a lakeshore through the old town of Montreux, through woods and Alpine meadows, to the clifftops of Rocher de Naye.

I start at the edge of Lake Geneva. The sun is shining; only much later will I realize that what I crave more than a map is a weather forecast.

At a cafe in the lakeside town of Montreux, where I begin my walk, I meet a girl named Melanie, who draws me a map — annotated with beautiful, tiny script — that leads me uphill past a castle: the Caux Palace. She adds details about its history, as a site of negotiations on the future of postwar Europe.

The path uphill quickly enters a narrow river gorge — lush trees and suddenly a different world from the lakeside. I am alone. Higher, the woods open out into Alpine meadows, which hum with insects. The grass is so thick that at times I lose the path and wade upwards through a sea of flowers.

I hike for three hours — past the castle and its narrow turrets — then sleep out in the open, on a viewing platform near the summit. I’m elated: I made it through my first day.

Day 2 24 miles, directed by two cheesemakers and a retired schoolteacher, I walk down then up again, twice over, through two river valleys and past countless cows.

The next morning, I head downhill toward a farm near Col de Chaude, a mountain pass where two cheesemakers draw my next map. First, though, is breakfast: cream piled on bread with a big wooden scoop. Meanwhile, a huge cauldron of milk heats over an open fire, on its way to being cheese.

Their map is simple: down from the farm, across a valley beside a dam and up toward a pass. Almost all the detail is in the house and the cowshed — there are five doors on the shed and a big chimney on the house, because, they say, “that’s where we make cheese over the fire.”

This teaches me something unexpected about maps. I was asking people how to get somewhere. But more often than not, what they illustrate were the things to which they pay attention. For these farmers, what is important is the number of doors on the cowshed and the limits to the valley they call home.

Later that day in a cafe in Château d’Oex, I talk to Charlotte, the retired schoolteacher sitting next to me. She orders ice cream for lunch. “I have watched my weight for 60 years and now I don’t care anymore,” she says.

Her map includes the number of meters I’ll need to climb and descend to reach the next valley. She remembers them exactly because she once ran over these passes.

Our attention is a gift. Reading maps is an act of empathy. They tell us as much about the person who made them as they do about the world.

Days 3 to 5 63 miles, from the gentler hills around the town of Gstaad into the higher Alpine terrain of the Bernese Highlands.

In my tent at night I’ve been reading Homer’s “Odyssey.” I’ve learned that in the ancient world, before hotels, travelers relied on the kindness of strangers — on expectations of what was called xenia, or hospitality — to form bonds with those who might otherwise have turned them away. Hosts also provided help for a guest’s onward journey.

I stop at a farmhouse, still ragged with sleep from my camp on a mountain pass. Through the half-open door an old couple and their grandson are eating breakfast. They have been up since dawn to milk the cows. They invite me in for coffee, bread and jam.

The farmer, Rudy, carefully draws me a map in between his morning tasks. He is busy, he says, but he wants to make me a good map: “I don’t want you to get lost,” he says. He gets out one of his own maps to check the compass points, then pencils them in. He tells me the farm has belonged to his family since 1664.

That night, having hiked along a winding path through crags and cliffs into Gstaad, and then along a rising stream toward a pass studded with farmhouses, I squeeze through a gap into an empty barn. I’m on the hillside above the town of Lenk and a thunderstorm has begun. I am drenched. I sit in the straw and eat the piece of cheese Rudy gave me as I left. I read about the chariot Nestor gives to Odysseus’s son to help him reach Sparta — help for the onward journey. I hang everything out to dry and listen to the roar of the rain.

The next day I follow the profile map that a man near the village of Adelboden drew for me, including where to find a “freezing shower.” I avoid it and swim in Oeschinen Lake instead, before sleeping in the grass of a meadow above.

Atop the Sefinenfurgge Pass, I ask two women, Lillan and Dora, to draw me a map to take me farther east. They work together, laughing wildly while they produce a picture that’s mostly of cows and flowers. Lillan is Norwegian and Dora is Australian. They are friends who haven’t seen each other in years but who have come to hike here together.

Once they finish, one of them says, “You thought you were asking us for something, but actually it was you who gave us a gift.”

Day 6 27 miles, past the imposing north wall of the Eiger, then over a pass toward the glacial Reichenbach Falls, made famous by Sherlock Holmes.

On my second climb of the day, up a mountain pass called the Grosse Scheidegg, I play a game to take my mind off my aching legs. It’s simple: Guess where the path will go next.

The map I’m using was drawn by Susana, a Portuguese woman who married into a local family and now runs a mountain refuge near the village of Grindelwald. The map mostly shows me the refuges I’ll pass, and what I should eat at each — which is delightful. But I’m also exhausted, and my guesses about which way the path will go are often wrong.

I have a habit of looking ahead. Even when doing something I love, I often imagine what’s coming next. I realize as I walk that not having a phone or a proper map — and thus not knowing what’s around the bend — has snapped me out of the habit. If I don’t know what’s coming, I can’t imagine myself there. Suddenly I’m present and engaged in a way I rarely am.

I look up to find a falcon hanging in the wind, caught in the roar of the air. It swoops, veering away down the valley.

Late that evening, I stumble into Victoria Restaurant, in the village of Meiringen. I eat the best meal of my trip. Simon, the chef, draws me a map that points uphill past several springs to the top of a mountain, where he’s added the label “Power Energy Stone.” It’s a special place, he says.

There’s a hotel above the restaurant. I stay the night, glad to have somewhere dry to sleep. In the morning I’ll go looking for magic rocks.

Days 7 and 8 43 miles, past three lakes (I swim in the second) and up a long valley to the Surenenpass, home to what I think might be the prettiest church in Switzerland.

Nature is a murky concept here. In spite of the mountains, the landscape is very manicured: grazing meadows, clearly marked paths, carefully managed woods. What’s wild is well hidden.

In the evening I see a fox crossing a meadow above the town of Engelberg — all fur, and so light on its feet that it looks like a marionette: afloat, barely touching the stage. Marmots, a pair of them, very young, peer at me from across the path. They’re gone so quickly I barely see them move.

The curated landscapes make Switzerland the perfect place for this kind of adventure. It would be foolhardy to do this in Tasmania, where I’m from, or in the American West — places where you could really get lost. Here, yellow signs point to well-maintained public trails. (An article of the Swiss Constitution mandates that footpaths and hiking trails be maintained.) Villages and trains are never far away. Even with roughly sketched maps, it is possible to (mostly) not be lost.

In any case, Kris, a solo Danish hiker I meet beside the Trübsee Lake, draws me a map. I ask her for a weather forecast. “Rain all week. Maybe snow.”

Days 9 and 10 43 miles, through the original heart of Switzerland and the turquoise lakes of the canton of Glarus.

Our brains, what the neuroscientist and philosopher Andy Clark calls “prediction machines,” get better over time at anticipating reality. Often we can imagine the world so well that we no longer have to look at it. And so, in familiar surroundings, it’s rare that our senses alert us that we’ve made a mistake — that what we first thought was a shadow is really an ibex poised under a tree in the dawn, for example.

Predictability is a privilege. It makes daily life easier. But it’s also a curse. By not paying attention, we don’t see the unexpected. We aren’t looking at the hillside trying to work out if the hand-drawn map we have is upside-down.

Before this trip, I imagined all the hours I would be able to simply think while I walked. What I didn’t account for is how much time I would spend thinking about whether I was lost. I also didn’t realize what I’d see when I paid attention to uncertainty, or how slowly time would pass when I had to look so closely at the world.

I walk through the sprawling canton of Schwyz, along a path made of huge granite slabs, following a map drawn by Peter and Andrea, two cheesemakers whose farm I pass. This is the heart of Switzerland — the original cantons that formed the Old Swiss Confederacy, the precursor to the modern-day country. I hardly see another person all day; it feels like the most isolated place I’ve been.

The next morning, after camping in a damp meadow above a lake called the Klöntalersee, I stop for breakfast at Gasthaus Richisau. A couple working at an artists’ retreat there draws me a map to get me to the Walensee, a lake near the border with Liechtenstein. They cannot understand why I insist on walking in the rain. They draw a bus on their map. “Why don’t you take this?” they ask. “You won’t get lost. It always leaves on time.”

Days 11 and 12 47 miles, through the craggy peaks and clifftop paths of northern Switzerland, toward the Rhine.

As I get closer to Lake Constance, my endpoint, the rain falls harder, until it is snowing sideways. I’m nearly blown over. It’s freezing, and so I start to run downhill to warm up. I laugh at how silly this whole thing is — and I’m still laughing when a tractor drives toward me. The farmer inside is dry and warm. He looks at me and laughs, too.

A man called Jon draws me a map of how to cross the canton of Glarus, which is bookended by the Klöntalersee and the Walensee, two exceedingly pretty lakes. With the inclement weather behind us, we forage for blackberries while we talk. He is there to BASE jump with a wingsuit and is camping by the lake in a van. His map is marked with cliffs and valleys — and the airport, which I guess one has to watch out for when you’re also a kind of flying machine.

Later, Chris, an American who has lived for decades nearby, draws me my final map. He has climbed and skied all over this region, and his map is among the most detailed of all: couloirs and climbing areas. I want to go in every direction. There’s material here for a lifetime of wandering.

When I finally get to Lake Constance, I jump in, despite the cold. Afterward, I calculate that I’ve walked about 250 miles. I largely avoided getting hopelessly lost.

After my swim, I walk along the lake to the train station. The timetable is printed on the platform, and the train arrives on time. Sometimes predictability is a blessing.

Publisher: Source link

Latest Posts

-

31 July 2025

-

26 July 2025

-

14 July 2025

-

01 July 2025

-

07 August 2025

-

29 July 2025

-

20 February 2025

-

04 February 2025

Newsletter

Sign up for free and be the first to get notified about new posts.

Get The Best Blog Stories into Your icountox!

Sign up for free and be the first to get notified about new posts.